Shadow of the Colossus: An oral history

Celebrate the 20th anniversary of Team Ico’s PlayStation 2 masterpiece by looking back with 11 people who worked on it (and three who didn’t).

Sitting down for an early 2000s internal Sony pitch presentation, Shawn Layden noticed something unusual. He was watching a concept video for the next project from the team behind cult-favorite adventure game Ico, and he thought the music sounded familiar.

Layden, then vice president of international software development at Sony Computer Entertainment Europe, loved what he saw of the game, which shared Ico's ancient, pale art style but added giant monsters players could climb and kill. If it was anything like Ico, he figured, he was sold — and a more commercial take on the concept seemed like a no-brainer.

He couldn't place the music, though, noting that the track fit perfectly as it built and welled up while characters on horseback raced across an open plain. Compared to Ico's confined interiors, the world appeared grand and expansive, with the audio layering on the feel of a Hollywood blockbuster.

As it turned out, there was a good reason why.

"Later on, we found out that was actually the theme music to the original Spider-Man movie," says Layden, referencing Sam Raimi's 2002 film. The music was placeholder — meant to get the tone across for the pitch, but not to be released to the public (though a fan has since recreated it). "We probably violated some usage rights," says Layden. "But, hey, it was 20 years ago, no harm done, and Sony owns the Spider-Man stuff anyway."

It's the kind of development anecdote that, for most games, wouldn't be particularly notable. It's not uncommon for teams to use unlicensed songs or assets for internal pitches, and the track never made it into the final game.

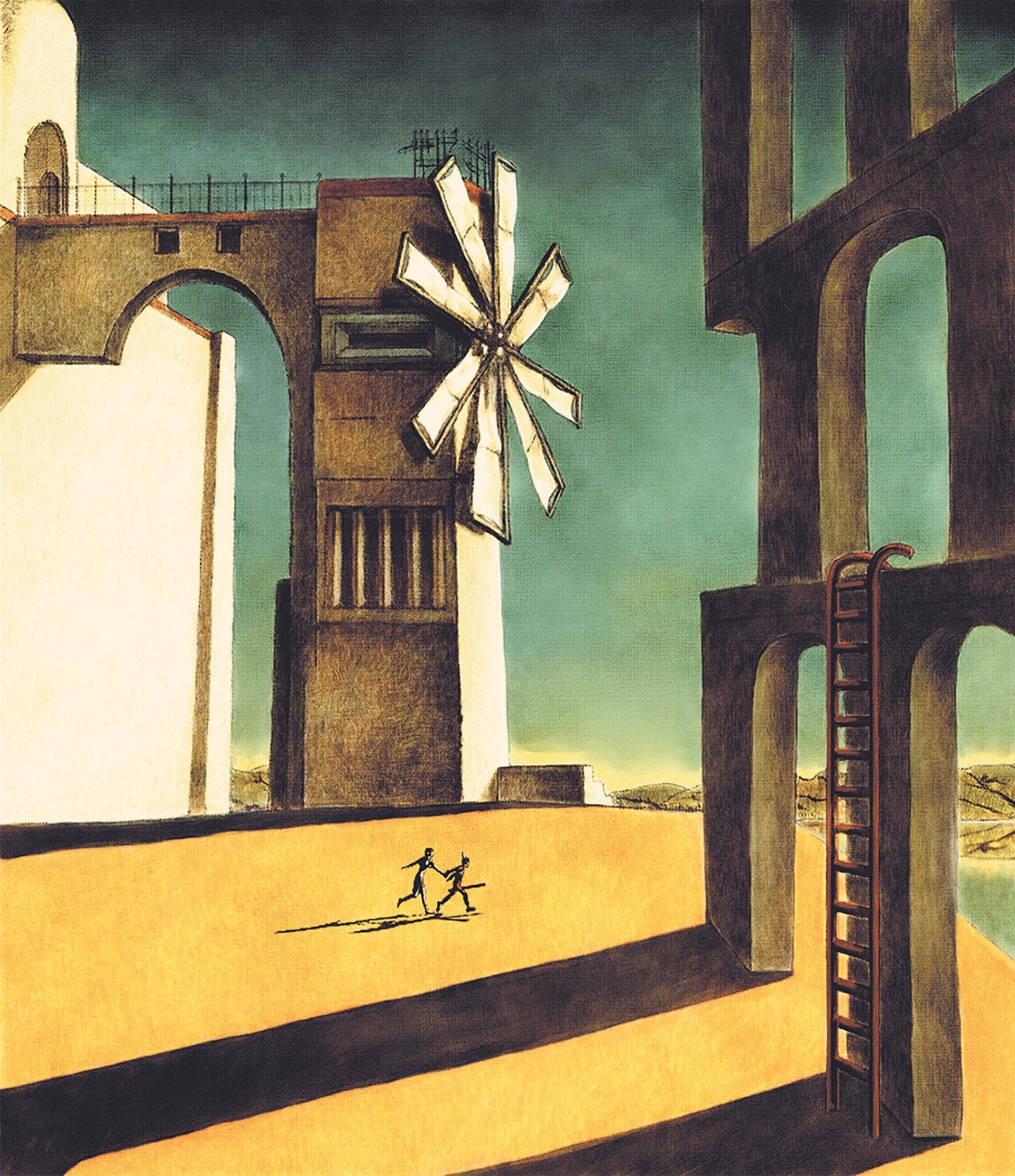

But Shadow of the Colossus isn't most games. Over those 20 years, it's developed a reputation as a minimalist, poignant experience. The kind of game that feels unaffected by pop culture. To some, it's the best example to date of a game that should be considered art. Which makes for an unlikely connection to something as colorful and mainstream as Spider-Man — or at least, that's how many fans see it.

Looking back on the game ahead of its 20th anniversary, we recently spoke to 14 people connected to it to get a better sense of how it came about, the challenges the team ran into, and the differences between what players perceive and what happens behind the scenes.

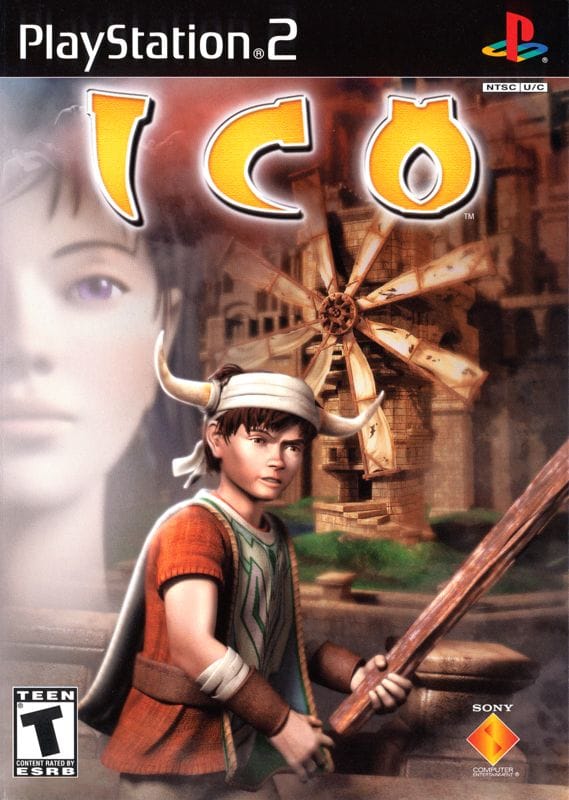

Given the controversial nature of Ico's U.S. box art, we tracked down the illustrator behind it and asked him if he was interested in a potential redemption arc by doing his take on Shadow of the Colossus for the game's 20th anniversary. He politely declined. | Images: Sony Computer Entertainment, MobyGames, Cook and Becker

A reaction to Ico and… Battlefield?

Ask Shadow of the Colossus director Fumito Ueda about the game's origins, and you'll get multiple answers. It was inspired by a game he was playing online. It was set in open fields because he was tired of working on a game set in tight spaces. It was based upon "fundamental sensations" he thinks everyone would want to experience, like riding a horse or climbing a tall building. And it was a reaction to Ico's success — or lack thereof. Ico was a critical darling and the poster child for proving games could be art, yet it was equally well known for underperforming at retail. Ueda took that to heart.

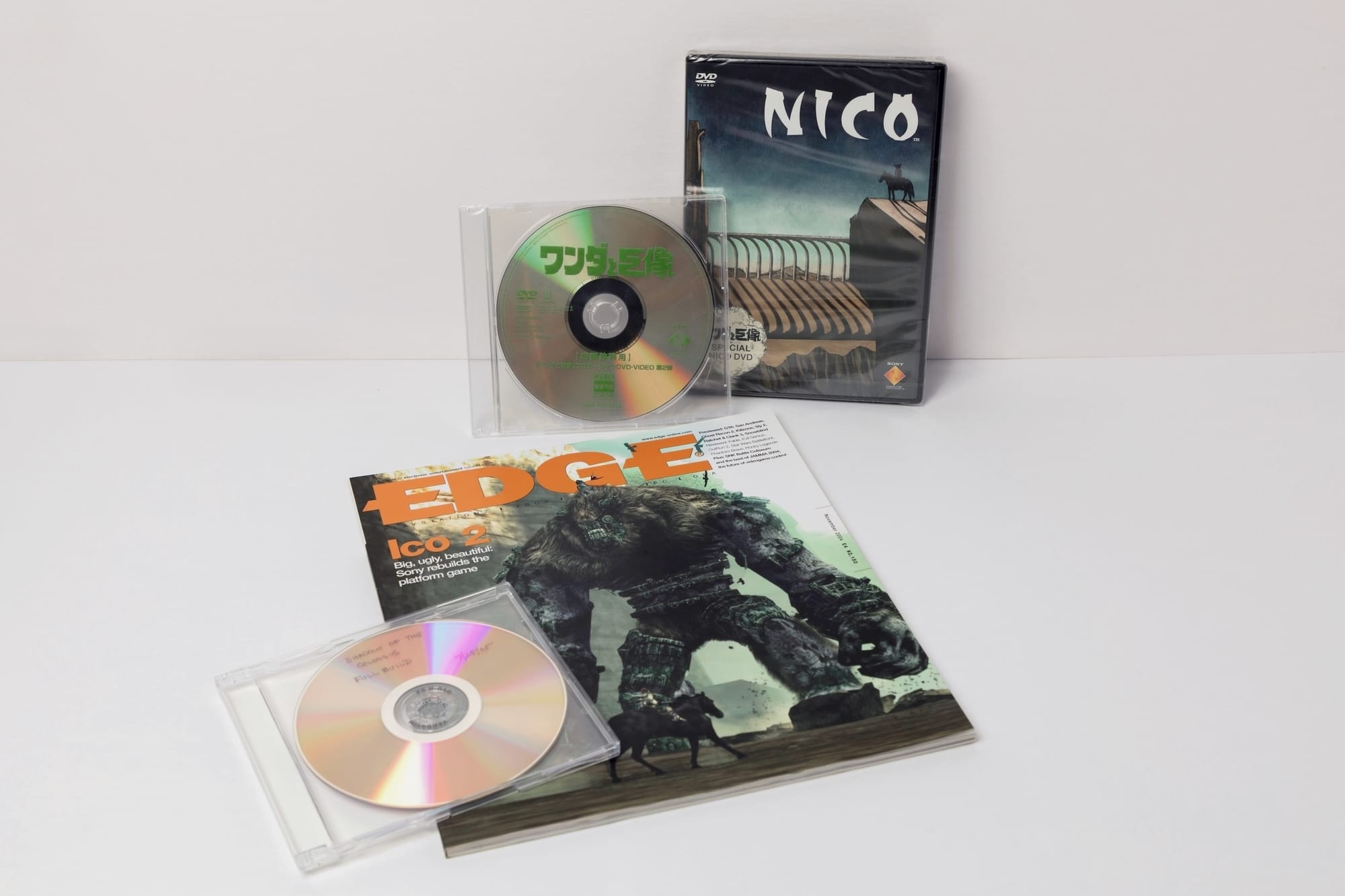

Fumito Ueda (director, Sony Computer Entertainment Japan): I remember it started as what we called project Nico [named after Ico and "ni," the Japanese word for "two"]. For Nico, we first created storyboards for the visuals we wanted to express. I remember inviting [line producer Kenji] Kaido to a restaurant called Jonathan's near the studio in Nakano-sakaue at the time and showing him, saying, "This is what I'm thinking."

Imogen Baker Othman (product manager, Sony Computer Entertainment Europe): There was a lot of speculation — would there be a direct sequel or something entirely new? It was called "Ico 2" for a while — in fact, it was called "Ico 2" on the [cover of Edge magazine].

Yasuhide Kobayashi (executive producer, SCEJ): Ico had some action elements, but not a lot. To find a better reception in the Western market, we thought our next game should have more action. That's what the conversation evolved into, as I remember it, and eventually that led into Shadow of the Colossus.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): Ico was highly acclaimed, but it didn't sell in huge numbers. That led me to think, Maybe games need at least a bit of violence. So, in Shadow of the Colossus, we incorporated violent elements like stabbing with a sword. Also, the protagonist of Ico was intentionally designed to be the opposite of the "cool-looking hero" that was common in games at the time. We deliberately gave the protagonist horns and a less appealing appearance compared to protagonists in other popular games. I wondered if that was also a reason for the lackluster commercial performance in Japan. So, for Shadow of the Colossus, we aimed for a character with a sleek, cool appearance and a stylish costume.

Yasuhide Kobayashi (executive producer, SCEJ): By that time, the Fumito Ueda "brand" was an established thing, and Sony recognized that fact too. As such, there wasn't really anyone at the company who could say "no" to him. My understanding was that Ueda himself wanted the next game to be a big commercial hit, so the managers at Sony more or less gave him a blank check to make whatever he wanted. I recall the project had a very smooth start.

[Nico wasn't just an early concept for Shadow of the Colossus; it was a multiplayer version of the idea. A concept video, which Sony released on DVD in Japan, showed characters on horseback tracking down a colossus, then one of them jumping off and stabbing it — much like the footage Layden described when talking about Spider-Man, but with a different soundtrack.]

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): In terms of inspiration, I wasn't playing many offline games back then. But I was really hooked on Battlefield 1942, an FPS. I felt immense potential in the experience of that as a competitive game, where you'd shoot at or help out other players you didn't know. That desire to create a network game — meaning a game where you play together, battle, or cooperate with others online — led me to start with the idea of a game where you cooperate to defeat giant monsters.

Johan Persson (lead programmer responsible for the original concept, Battlefield 1942): That is truly a surprise! It's such a different experience. [...] You tend to just assume these ideas were the result of someone having a eureka moment, waking up one morning, without any context.

Kyle Shubel (producer, Sony Computer Entertainment America): That was the first pitch that they made as to what they wanted to make, and that wasn't really going to come to fruition with the early stages of the Network Adaptor for the PlayStation 2. [...] But yeah, the [idea of] I'm going to stun it. I'm gonna tie its leg while you mount on top of it. I'll go in front of it and blind it while he takes it out — that concept, and then jumping back off onto your horses, and riding off in the sunset — yeah, if we could have pulled that off, everyone would be talking about this game.

Shawn Layden (vice president of international software development, SCEE): I guess there would be a question of, What would be the multiplayer mechanic? What would make it compelling? Could you track down a colossi on your own with friends and bring it down together? I suppose. But it's not a traditional skill base for that team.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): We probably hadn't gotten as far as testing multiplayer, or maybe we just connected two controllers on a local network and were able to move characters around. That was about the extent of it. We hadn't reached the point where you could play online. Personally, I thought we could attempt making a multiplayer game because we were developing within Sony's first-party studios. But looking at the production resources at the time, I decided that we couldn't realistically do it. To efficiently concentrate resources, we cut the multiplayer portion.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): I remember that part vividly. We barely even got to testing. What sticks in my memory most is how early Ueda decided to drop the multiplayer feature. I was impressed by how quickly he made that call. It was a choice between forcing the challenge or letting it go. Sure, there were people within Japan Studio who could have done it, but it would have become a massive undertaking.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): It felt like it would require other sections of Japan Studio to get involved and inflate the project.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): We were starting to lay the groundwork, but Ueda said, "We're stopping." I remember thinking he was a quick decision-maker.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): Compared to Ico, this game had to have the following: an open-world setting with dynamic loading to express infinite space; "deforming collision" where you cling to giant structures; and a quadrupedal animal for the horse. All of these features were already raising the bar significantly compared to Ico. We had nearly the same production team as Ico, and we knew network games were tough to make. Adding network support would also require the player to have more hardware to play, limiting those who could experience it. For these reasons, I decided to cut our losses early.

[In addition to discarding the multiplayer concept, Ueda set aside two ideas he had for other games following Ico's release — ideas that both would have required hardware that didn't exist for PlayStation at the time.]

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): Are you familiar with Norshteyn — the Russian animator Yuriy Borisovich Norshteyn? We were trying to make a 2D game inspired by his style, and the concept involved using a touch panel. This was before the Nintendo DS was announced, and I thought it was time to move away from conventional games that required lots of button presses. So this concept was the complete opposite of [an online multiplayer action game].

While the online game idea was geared more toward core gamers, this was a game anyone could play, even people who'd never touched a controller. Back then, we were already using LCD tablets for game development, so I thought, Wouldn't it be great if this became a gaming device? I came up with a concept combining a painting tool with Norshteyn's artistic style, made a video, and shared it internally. [...]

Of course, this was for PlayStation, but it wasn't about being constrained by the PlayStation hardware of the time. It was more about thinking about the idea holistically, including the hardware. What I want to emphasize is that this was before the Nintendo DS.

So that idea was based on animation, combining drawing with puzzle gameplay. The other was a VR game. This was before head-mounted displays were common, but I thought it'd be amazing to put on an HMD and enter the world of Ico. For example, how amazing would it be to lie on the rooftop of Ico's tall castle, looking up at the sky through an HMD? Or having Yorda in the next room, with a thin gap in the wall so you could see her by turning your head vertically through the gap. I wanted to challenge myself with a VR game based on Ico. [...]

For the puzzle game, I did use CG tools to create a video showing, This is the kind of game it would be. But the VR game was really just a concept. I remember posting the puzzle game idea on the company's internal planning bulletin board and getting feedback from a few people.

The making of our cover art

We hired Gravity Rush concept artist Takeshi Oga, who worked at SCEJ in another department during Shadow of the Colossus' development, to illustrate the cover art at the top of this story. Then, exclusively for paid subscribers, we talked to him about his process.

Pitching the game to other territories

Due to Ico's critical success, the development team didn't struggle to get a follow-up off the ground. At the time, though, that didn't guarantee the game would be released in other territories. Sony had shipped games like music/calligraphy crossover Mojib-Ribbon and virtual pet simulator Doko Demo Issyo exclusively in Japan, with the latter's main character, Toro, even becoming something of a mascot for the console there. So Ueda and Kaido needed to sell Sony Computer Entertainment America and Sony Computer Entertainment Europe on why they should release the game, which turned out to be easier in one case than the other.

Alison Lau (associate producer, SCEE): Maybe three times a year or so within Sony back in the day, we had a gathering of all of the international software teams. They had their headquarters in Japan, so it was people from Japan, people from SCEA, and people from SCEE gathering together. So in each of those meetings, the teams would discuss what kinds of titles are upcoming from their either internal or second-party studios occasionally. Talk about lineups.

Jeff Reese (senior manager of product marketing, SCEA): My second day on the job, I jumped on a plane, went over to Japan, where we had all the studios come together. And what they would do is pitch the ideas, their games, to other regions, which I thought was pretty interesting, because if you're going to develop a game — and these were hundreds of thousands, millions of dollars back then — you wanted to make sure it was going to be accessible across more global markets, right? You wanted to make sure you could actually get a good return on that. So I found it very interesting that they were pitching. And so when we were over there — I believe this is the first time I've heard of Shadow of the Colossus — and they went up, they pitched the concept. We didn't see any gameplay; we just talked about the idea. But the legacy of the studio had already kind of greenlit this for Japan.

Kyle Shubel (producer, SCEA): Apparently, this one had gotten pitched in the summer of '04 and got declined by [Sony Computer Entertainment] America. I got to see the demo that they'd given, which was really a videotape of a demo, and I went straight into the office with [SCEA director of product development] Allan Becker at the time and said, "We need to pick this up. This game has so much potential. We need to take it." And he said, "OK, let me make a couple calls." Called Japan, and they said, "Well, yeah, we'd love to have it [released] in America." [...]

Ico didn't sell well here, so it was passed on for business reasons [...] I don't want to say specifics as to who turned it down. But yeah, it was passed on for good business reasons, assuming the game was going to be like Ico.

Mark Valledor (product manager, SCEA): Yeah, I remember a little bit of that. It was mainly from a sales standpoint. It's like, OK, what are they really going to bring to the table? Should we spend our resources doing it? But I think ultimately, the powers that be wanted to support our developers. And you would have a segment of games that were built to be the moneymakers, right? Back then, it was the Grand Theft Autos; we had Gran Turismo. This was before God of War, but we'd always have our stable of moneymakers, but we also wanted to lead in technology and visuals. So I think because of that, those are the types of games — fortunately, the types of games that I worked on. So the PaRappas and Um Jammer Lammys, right? They were very unique, and you could tell that message from a PR standpoint.

Yasuhide Kobayashi (executive producer, SCEJ): No one ever told me directly that Shadow of the Colossus was turned down for a U.S. release, so I don't know much about that. Maybe that was just the sentiment of the U.S. team at the time, but I have to wonder if that sort of sentiment came from a time period when our team's relationship with the U.S. marketing department wasn't going very well. After Ico came out, I believe it was during a speech I gave to the media, but I said that the reason why Ico didn't sell well in America was because the packaging design for the U.S. version was not very good. The Sony marketing team got mad at me for that, and the relationship was strained for a while. So maybe that was part of it, though I never heard anything directly.

Shuhei Yoshida (vice president of product development, SCEA): We never turned it down. There were some questions about the game from the marketing team during evaluation, like "Why only bosses?", but in the end we convinced everyone that the developer is designing the whole experience, not bits and pieces.

Jeff Reese (senior manager of product marketing, SCEA): There was a lot of politics. Sony is a very interesting company, just because there are a lot of silos. There was a lot of competitiveness between the different groups. So you used that actually to your advantage a little bit, because each studio wanted to kind of compete and wanted to get to the top, wanted to be able to get the recognition.

Shawn Layden (vice president of international software development, SCEE): In Europe, we had a much more open view towards bringing games to the continent. We realized that you just can't only target games that are going to get 10 million units. The market's bigger than that. That's a whole different argument about today's market, but we'll set that one aside for a second. Still back in the PlayStation 2 era, we're looking for the breadth of offering. How wide is the portfolio? We've got some shooters. We've got some racers. We've got some fighting games. What else do we have out there? And certainly Ico, and laterally Shadow, were completely sui generis. There was nothing else on the market like it, and we always felt when we were at [SCE Worldwide] Studios, we either wanted to be the first or be the best. And definitely Shadow would be the first. And it turned out to be quite good — certainly, the best in some categories.

The Americans were always a bit more parochial, shall we say, about wanting to get behind things they knew they could sell a lot of — more "how best to leverage the market," rather than "how to educate the market on what else is out there, what else people should be looking at." But, in the end, everyone got on board.

Building Team Ico

Team Ico was not a continuous group over the development of Ico and Shadow and the Colossus. It took time to hire staff early on, and team members came and went over the years. Ueda and Kaido remained at the top through both projects, though, and were joined by Kobayashi partway through Ico's development, giving the group a sense of cohesion.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): When we first started Ico, it was just Ueda and me. We built the team from scratch. Back then, Ueda really emphasized wanting people "untainted by games." We hired his university friends and juniors, brought people over from other teams within the company, conducted numerous interviews, and gradually assembled the team. [...] Partly because we struggled to assemble the team, I feel a strong affinity to it.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): I think everyone feels that attachment to the team. Staff who have fixed ideas about "how games should be" make it difficult to take on new challenges. So we carefully selected people who weren't influenced by any particular style, but who had the skills. For example, they were really good at drawing, etc.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): Quite a few were people you brought in, right?

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): That's right. About half were friends and classmates or students from my alma mater.

Kyle Shubel (producer, SCEA): [Ueda] is your pinnacle creative. He has a distinct vision and trying to convince him otherwise is quite a challenge, so any changes you want [to things] that are near and dear to his heart, you have to convince him [they were] his idea. He had a grasp on everything about the game. He was intimate with programming. He was intimate with the art. He was very, very in touch with every aspect of the game — sometimes to the detriment of the game. You know, if this team has gotten the sword colossus ready and he's not ready to go through and proof it, they had to go work on something else to potentially have to come back when he had time. So he was the bus driver, and everyone was riding to his destination. And I say that with the utmost respect and reverence for how he handled it.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): I think from the outside, people view me as the "artistic type," the one who draws pictures and comes up with big-picture concepts. But that's not really the case. I guess I shouldn't say too much because it might shatter my image, but I'm actually primarily concerned with how to build the game efficiently rather than with creating the game's environment. What do you think, Kaido?

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): Ueda is extremely practical. He's more of a designer at heart than an artist, and he has an engineer's mindset, too. Conversely, I'm the more free-spirited type and enabler, and casually encouraged Ueda, saying, "I think you should try this and that."

Yasuhide Kobayashi (executive producer, SCEJ): Between Ueda and Kaido, I think there was a mutual need to respect one another, or watch out for one another. Obviously, Ueda is quite talented and has a lot of achievements under his belt, but the same goes for Kaido. Kaido has his own achievements in game design and game direction, and he was also a person who commanded respect within his field. So their projects saw two very strong, individual personalities working on the same single project. In that sense, I think it's only natural that they'd butt heads every now and then. That being said, I think each of their responsibilities were very clearly outlined, so although their opinions may have clashed from time to time, I would say that their projects turned out very well.

Kyle Shubel (producer, SCEA): You've heard horror stories about game developing in the '90s and the aughts, when [teams were] working ridiculous hours and stuff like that. I remember coming in early on the project, and it was like, "Is Kenji in?" You know, my counterpart, the producer. "Is he around?" "Oh, yeah, he's at his desk." And I walked by the cubes, and I looked at his desk. No one's there. And I noticed — "wait a second" — he had a jacket hoodie that he lifted up his keyboard, tucked his hoodie underneath, and he was underneath his desk, sleeping. Because he'd been there for two days straight. And he was catching some sleep when I happened to get into the office. I was like, Dude, I so don't want to wake him up. And I just pushed this off. But they were just — they believed. They were all very much hardcore believers that this game had to be made, and it had to be right.

Yasuhide Kobayashi (executive producer, SCEJ): One of the most notable things about Ico is that no one ever went home. People were practically living at the company. Typically, you'd go home at night after work, but not for this project. [...] It was the same [for Shadow of the Colossus].

Extended interview

Parts of our interview with Fumito Ueda and Kenji Kaido ended up on the cutting room floor, so we put together an extended cut for paid subscribers. Click through for insights into Wander's character design, Warp's influence on Team Ico, Bluepoint's remaster and remake, why Kaido left Sony, how to keep motivation up when working on a long development cycle, and why Ueda feels conflicted about the game's ending.

Getting international feedback

Working inside Sony Computer Entertainment's corporate headquarters in Japan, the Shadow of the Colossus team kept largely to itself for the first couple of years, building the game without extensive help from other departments or divisions of Sony. Even Kaido and Kobayashi say they were reluctant to offer creative input, deferring to Ueda on the game's vision.

As the game got further into development in 2004 and 2005, though, its footprint at Sony grew larger, with production, marketing, localization, quality assurance, and other staff from Sony's American and European offices joining the project. The development team started sending out regular builds and getting feedback from different parts of the company, and by most accounts, didn't run into the types of controversial decisions that sometimes result from international feedback or focus testing, like what happened with Ico's cover art.

The Western releases ended up with different box art (focused on showing a colossus' face to draw attention), a different title ("Shadow of the Colossus" instead of the literal translation of the Japanese name, "Wander and the Colossus"), and a number of tweaks based on feedback from Sony's international offices.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): [We didn't get a lot of requests], but we did get some. The overseas producer understood the direction of the project, so they weren't unreasonable demands.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): The overseas producer wasn't deeply involved. What stood out was how little they interfered with development compared to other titles.

Kyle Shubel (producer, SCEA): I was out there every three months, meeting with the dev team and going over production milestones, so I had some influence. But honestly, Kenji Kaido was the producer of the game, Fumito was the creative director, and they owned that game.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): For Ico, we got comments like "There aren't enough enemy types" and "The protagonist's horns point backward, making them look like a ponytail and making the character appear female, so you should change the angle of the horns." We did fix the horns, but we couldn't address the enemy types due to the production schedule. For Shadow of the Colossus, since Ico received such high praise overseas, they may have felt compelled to let us do our thing.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): That was definitely the case.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): Kaido, do you remember if there was any feedback for Shadow of the Colossus from overseas?

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): Not at all. I remember being asked, "When is it coming out?" constantly, not about the game content itself.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): That was probably because they wanted to make marketing and promotional plans.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): Probably. They asked at every opportunity. Even in casual conversations, it was, "When is it coming out?"

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): I suppose it was also meant as a compliment, as in, "We're looking forward to it."

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): Yes, I think that was part of it too.

Kyle Shubel (producer, SCEA): I would try to point out anything that I saw that was, "This might go better in America if..." or, "This may be a little bit too nuanced for the Westerners. Make the doves more prevalent." Things like that. It's not that I added the doves. I just made them more in your face.

John Hight (director of external production, SCEA): I'd say probably my major contribution was in getting the team to, believe it or not, tone down some of the bosses and make them easier to defeat. [The fifth boss] did just a horrendous amount of damage, so you really couldn't take many shots before you died and you had to restart. And it was funny because I was getting feedback from our QA department, too. It's like, Man, these bosses are so hard. And, you know, QA has to be very good. They tend to be the best players of the game. [...] But in this case, the QA team was really struggling, and that was a big warning bell for me.

It was funny, because the feedback I got from the development team — and even our testers in Japan — was like, Oh, you know, you people in the U.S., you're just not great players, because you should be able to defeat this easily. But I did get them, finally, after a bunch of rounds [of feedback], to agree to tone it down a little bit, especially the very last boss. Malus was — nobody was taking that boss down. It was impossible, at least in the initial builds that we were looking at.

Kyle Shubel (producer, SCEA): Adding save games was a big thing. We got them to add the shrines in, because it was just one of those — you would play, you'd get six hours in, you'd die. And it'd be like, Oh, God, this is a roguelike before there were roguelikes. [...]

Being able to grab onto the birds [was another]. Not the doves, but the hawks that they jump and grab onto — and you can ride one, but it drifts down. That was something we requested, because apparently everybody jumped and tried to grab onto them. And it didn't work for quite a while. [...]

We moved the QA almost exclusively to the West so that [the team in Japan] could work all day long and hand off a build, and we could start doing the follow-the-sun. That was about when Sony started doing that, and we had a lot of the test team down in San Diego rather than being in Japan.

Kelly Bollinger (game test engineer, SCEA): I found this out later, but the entire dev team in Japan was very, very secretive. We didn't have any documentation because they just kept everything in-house, so we thought we were [the only] ones testing the game. They were absolutely testing the game, but we were testing from a black-box perspective.

Kyle Shubel (producer, SCEA): No game has the luxury of infinite QA. So our QA guys were like, Wait, there are artifacts? And they would beat it a few times, and it's like, I can glide now! You start getting that uncanny feeling from the QA guys, like, Oh, man, we've gotta beat this game like 10 times in a single build, and that's gonna take this many hours. How are we gonna do this? So there was a lot of pass-the-controller, 'round-the-clock QA testing to try and get one save game that was that far in.

Kelly Bollinger (game test engineer, SCEA): We were trying to get into every nook and cranny on the map. [...] You start out at a big cathedral tower where you've laid the girl down, and she's kind of your focus, your impetus for killing these colossi. We noticed that this thing was just giant, and it did have moss growing around the sides of it. So we tried climbing up the moss, because that's what you do in Shadow — you can climb on things. And you'd run out of stamina before you got to anywhere you needed to get. But we also figured out that each time you beat the game, you start over in new game plus and your stamina bar is just a little bit bigger.

So we had had our speedrunner beat the game, like, 16 times in a row so his stamina [gauge] was big enough, and we were able to climb a really far way up the castle, which you "weren't supposed to be able to do." And we got into this huge secret room in the middle of the castle that was full of bugs, but that was because the devs never expected anybody to get there. They were like, How did you even find this without, like... — we didn't have cheats or anything; we had to do everything legit. So that's the most memorable one, because I know later on when they did remakes for the PS3 and the PS4, they made trophy achievements if you could make it to that secret area.

Sony's official screenshots, both for the PS2 original and the PlayStation 3 remaster, often highlight the game's sense of scale. | Images: Sony Computer Entertainment, MobyGames

From one monster to another

One of the smoothest parts of Shadow of the Colossus' development, according to Ueda and Kaido, was the game's score. Danny Elfman's Spider-Man theme was never a realistic candidate for the actual game, but the team had another film composer in mind. Kow Otani had composed the soundtracks for the mid- to late-'90s Gamera trilogy, giving him plenty of experience working with giant monsters.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): Shadow of the Colossus is an action-adventure game. It has a dynamic, action-packed feel, so we were looking for someone who could compose that kind of music while also expressing the lyrical quality from Ico. Since Otani had also recently composed music for the newest Gamera film, we approached him. We felt he could express something colossal in the music.

Kow Otani (composer, freelance): They were very careful to explain the game's world to me to help me understand what the game was about — so much so that I was so invested in the game that I wanted to do more than they assigned. I remember that I already had the music for the prologue and epilogue in my mind from the first meeting.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): First, we had him create demo tracks. He made several pieces, and when Ueda requested, "Could you tweak this a bit more?" the revised versions arrived the very next day. That responsiveness really stood out. He was also very cooperative in writing many variations afterward.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): Otani is older than us, a legend. So we were worried, Will he be willing to take requests for retakes? But it was totally fine, and we were convinced he was the right person for the job.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): He's also very humble, asking things like, "Is this how you want it?" He gladly accepted retakes, no matter how many times, saying, "If it makes it better..."

Kow Otani (composer, freelance): I had worked with a lot of movie directors by that point, so I was used to working with very temperamental directors. It was a common occurrence for directors to give me instructions one day and change their minds the next day. So, those experiences taught me resiliency. I have a lot of compositions at my studio filed under "send to trash."

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): Otani rode a Harley-Davidson back then, and I rode a Vespa. We really hit it off talking about motorcycles. I remember when my bike broke down and I was late to a meeting, he said, "I ride a bike, too — a Harley," and that really brought us closer.

Additionally, we were trying to implement a system where the music would seamlessly change depending on whether the protagonist was gaining or losing the upper hand during each colossus battle. We made this wild request: to compose the music in sections so we could program the music to seamlessly match the gameplay, no matter how they were combined. Unfortunately, in practice, it ended up being too hard to tell when the transition was occurring. So for the final product, we had the music crossfading between the advantage and disadvantage themes. The technique Otani worked so hard on wasn't implemented.

Kow Otani (composer, freelance): Ueda wanted the music to be dynamic and change depending on what was happening in the game. He wanted the music to reflect the player's performance in the game in real time. [...] This is a very constraining rule for a composer. Because in order to switch between two different music styles smoothly, it has to be the same key and the same tempo while also being melodic and pleasing to your ears. It was nothing that I'd ever tried before. I think any composer would have a difficult time understanding how this could work.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): Another thing was, as with Ico, we had to commission the music tracks long before the game was finished. We'd make a list like "X number of colossi battle tracks, desert tracks, horse-riding tracks..." and commission them prematurely, not knowing what the end product would look like. As the game developed, things changed from the original plan, leaving us with a huge surplus of tracks.

We could have left them out of the soundtrack, but we wanted to use them since he made such an effort to make all these tracks, so we squeezed them into the ending scene. After listening to all the music Otani created and watching the game footage, we searched for any bar, any fragment that might fit into the ending. This is why the music for the ending cutscene became a sequence where the music switches continuously.

Staying on schedule

Despite the team's dedication, it took just over four years between the releases of Ico and Shadow of the Colossus. Compared to the two games Ueda would go on to make later, each of which has taken closer to a decade to develop, four years looks efficient by comparison. But Ueda, Shubel, and others all say Shadow's development cycle didn't feel short, especially in the PlayStation 2 era, when games were regularly developed in a year or two.

This, in part, had to do with the game's scope. Ueda has often spoken about the original plan for the game involving the player tracking down and fighting 48 colossi — a number that dropped to 16 in the final product.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): We ran into plenty of challenges, but first and foremost was the schedule. Things didn't always progress as planned, and deadlines just kept closing in. On top of that, numerous bugs popped up, stalling development. To name one specific thing — Kaido probably remembers this, too — the enemy AI [behaviors] slowed us down. The game has 16 colossi, and initially, all of the 16 were being developed separately.

It might seem obvious in hindsight, but in reality, we only needed about four or five colossi types: bipedal, quadrupedal, serpentine, avian, and so on. For some reason, we started developing them all separately. At a certain point, I consulted with Kaido and realized, This is not efficient, and redesigned the system myself. I consolidated the quadrupedal and bipedal types, etc., restructuring it that way. For issues like those slowing down development, we'd implement ideas to shorten the schedule. It was a constant cycle of that.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): My constant concern was, How can we secure the schedule and budget? I knew we'd get it done because everyone was working so hard, and I knew the more time we had, the better the game would be. To ensure quality, I needed to secure a schedule that allowed us to push the release as far as possible. To do that, I was constantly negotiating with the studio head.

Yasuhide Kobayashi (executive producer, SCEJ): Kaido really worked hard to try to make Ueda's desires come true, to allow Ueda to do what he wanted to do. So Kaido was in the most difficult position. He was the producer, so he had to basically stand in between me and Ueda. We would have discussions about budget management, schedule management, and things like that. I think Kaido was in a tough position, caught between my demands and Ueda's passion for this work. [...]

We had weekly progress meetings about the schedule. This was a meeting that we had for all titles at Japan Studio, not just Shadow of the Colossus. Then, once a month, we would have larger-scale schedule meetings, too. And there was one time when Kaido had to report to me in this meeting to say Shadow of the Colossus was running a little bit late. So I had to sort of pressure him to come up with a plan on how to recover from such a delay. Since we had these meetings every week, it was a very repetitive process, and not very fun for him, I think.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): Back then, it was all on me.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): I never got that kind of pressure directly. And this may come off as crass, but my stance was, How can I help Kaido 'fool' the company? I provided Kaido work-in-progress assets to present to upper management so it would seem like we were making great progress, to create the illusion that more of the game was completed than actually was. We'd skillfully edit recorded footage instead of playable content, layer existing music tracks, and make it look like it was running smoothly. That's how we'd deceive them [in an effort to extend the production time and budget].

So, to answer the question of why we were able to take so much time in development? One, Kaido acted as a buffer, but it was also because there was this internal acknowledgment that the game's visuals were amazing. I think it was hard for them to rush us because of that.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): I definitely used that to my advantage, creating fancy Gantt charts [showing the production timeline] and convincing them, We can absolutely do this. We'll deliver results.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): It never went exactly as planned, though.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): No, I knew it wouldn't, but I was good at making excuses. I don't remember the details, but I worked on ways to make it look like we were making progress. Then, at the end, I'd bring the timeline up and say, "Let's extend it a little longer."

Yasuhide Kobayashi (executive producer, SCEJ): Of course, I wish we had a bigger budget. The thing is, the way they developed the game, even if you added a bunch of people to the development, it wouldn't have changed how fast it went. That is because Ueda was very exacting about checking the quality of every aspect of the game. If you expanded the budget and production, it would have produced even more items to check, which would result in a bottleneck because Ueda is just one person. So increasing the budget, increasing the size of the team... that would just have ballooned the production time, and I suspect that ultimately, the output wouldn't change very much. Basically, the way Ueda's team worked, if you didn't increase the total budget and the development time, it wouldn't result in a game of higher quality or volume. I felt that way then and still do now.

Kyle Shubel (producer, SCEA): [Kenji] was trying to juggle a great deal and the creative was driving the bus, so it wasn't always the, No, no, we have to do A, B, and C for this milestone. It would get two-thirds of the way into the milestone, and Fumito would decide, "That colossus doesn't work. We're gonna move him somewhere else in the game, and we're gonna make a new one." "But we only have four weeks left in this" — it's like, Ah! So Kenji had to juggle a little more than your average producer in support of Fumito's... I keep wanting to say "crazy ideas," but they aren't crazy, because look at how well it turned out. So it's just one of those — Fumito would get a bee in his bonnet, and he would force that to be the next thing they worked on so he could get it out of his head. So Kenji was often very tired when I saw him.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): We faced high hurdles like deforming collision, the open world, and network features. But back then, both Kaido and I were young, and we had this attitude of, We can do it all, right? If it were me now, I'd definitely stop myself. It's tough enough to do one thing well; trying to do three or four simultaneously is reckless. But precisely because we managed to clear those difficult hurdles, I think that's part of why the game was so highly regarded.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): We were fooled a bit by the PlayStation 2's specs, too.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): You mean the "Emotion Engine," right? The PS2 was marketed as being able to express emotion, but I wasn't really conscious of that aspect. In the end, we did pride ourselves on making something emotional, but we didn't advertise it.

Kyle Shubel (producer, SCEA): There was brief talk [of moving the game to PS3, and then] I think the foot from above came down and said, "You're shipping this fall."

Yasuhide Kobayashi (executive producer, SCEJ): The one thing that actually did become a problem — I don't know if you would call it a problem, but a discussion — was figuring out when to release the game. That was the thing we struggled with the most. [...] If the team had done everything it wanted to do, it could easily have taken 10 years to finish. That's why I believe it was the right call to stop the development and release the game when we did. If [the team] had been allowed to do everything it wanted, it would have just kept going with no end in sight. [...]

I seem to recall that the U.S. version of Shadow of the Colossus came out a little bit earlier than the Japanese one, so that version actually contains a lot more bugs. Basically, the American marketing team intended to release the game regardless of what state it was in, so we were pressured to hand over the master ROM. [...] Normally, in a development schedule, you'd figure out when the master build is going to be created, and then you'd release the game after that at a convenient time period. But because Shadow of the Colossus was a tentpole release for Sony in that time period, it didn't really matter what the game's development progress was. It needed to come out on the day they wanted it to.

Jeff Reese (senior manager of product marketing, SCEA): I would say the forcing function was retail. So, you sit with Best Buy, it was nine months out; Walmart, nine months [or] 12 months out, to be able to go and say, "We've got something that we want to release."

Shawn Layden (vice president of international software development, SCEE): You kind of grow to expect certain outcomes. Ueda-san's game was always going to take a little bit more time than we thought. And I think a lot of us had that sort of priced into our model around it. I don't particularly remember the [last] 18 months of Shadow to be particularly egregious in that way. It kind of flew over the mark that we had set for it, but we landed in time. It was fine.

Giant steps

Shadow of the Colossus shipped on Oct. 18, 2005, in the U.S. — a rare case at the time of a game developed in Japan debuting overseas. It made it to stores in Japan a little over one week later, and shipped in Europe the following February. Like Ico, it became an instant critical success, with reviewers loving the blend of emotional storytelling and large-scale action. Unlike Ico, it became a commercial hit as well.

John Hight (director of external production, SCEA): I think the basic assumption was that it was not going to sell the kind of numbers that God of War was going to sell. It was not seen as a tentpole game, but rather, demonstrative of the diversity of Sony's portfolio of games. And especially in Japan — at that time, there were literally thousands of PS2 games coming out every month.

Typically [Japan] was a pretty aggressive market for Sony, where a game would come out, it would be hot for a couple of weeks, and then [people would] move on, because there were just so many games during that heyday. And I think there was a concern that Shadow would be one of those games that everyone was talking about and loving — and then [they'd move] on to the next thing after a month.

Jeff Reese (senior manager of product marketing, SCEA): Not a lot of people were enthusiastic. Not a lot of people thought it was going to have great sales.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): We rarely received praise for the game during development. The only exception was a programmer called Jinji Horagai [who went on to co-found GenDesign with Ueda], who boldly declared, "This will sell a million copies!" He probably had no basis for it, but it left an impression.

Kyle Shubel (producer, SCEA): The goal was, like, a half a million. I'm sure there was a specific number for it, but that was always my goal — I wanted a half million U.S., and when we beat that in the first year, I was ecstatic.

Jeff Reese (senior manager of product marketing, SCEA): I think we surpassed 50,000 sales the first week, and we had targeted 18 [in the U.S.]. So I think that's the part that [stood out] — you have low expectations, and then as you come out, you go, "Holy cow, this is really big."

Kyle Shubel (producer, SCEA): I want to say it was, like, 800,000 units in the first year, [and] I want to say Ico sold 120 [thousand]. So it was wildly successful from that standpoint. Was it God of War selling 3 million units? No, but it was 20, 25 guys. You know, they grew past that [team size] at the very end, but this was not as expensive of a game to make.

Shawn Layden (vice president of international software development, SCEE): I think the market was ready for it. We told the right story in the marketplace. It didn't turn into a 50-million-unit seller, but it was never supposed to.

Kyle Shubel (producer, SCEA): The U.S. was the lead territory. It sold 800K in America. I can't remember in Europe — it was like 450 to 500 [thousand]. And it was like 220 [thousand] or something in Japan. [...] Globally, it was over a million-unit seller, which, when you compare that to much less for Ico, and [add in that] the press was gaga for it, everyone was talking about it, and the interviews were all very positive, everyone was happy with the game.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): Thanks to the efforts of the SCEA team and related departments at the time, it sold quite well in North America. It also sold better than Ico in Japan, and globally, we reached the 1 million mark.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): Honestly, I never heard the exact figures.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): That kind of information wasn't disclosed much back then. In terms of success, it sold better than Ico, and it was profitable. But what surprised us most was winning Game of the Year at the GDC Awards.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): We did expect it to be nominated.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): We thought we might win an art or music award, but we never expected to win the Game of the Year award. That was really rewarding.

John Hight (director of external production, SCEA): In that first year, [copies of the game] quickly sold out, and they became super rare. When you're at Sony, all your friends are asking you, "Hey, can you get me a copy of this game?" And you can usually hook up your friends, but in this case, Shadow was gone. I used to get a copy of everything, and I had, like, five copies of Shadow, and I finally went down to the point where I'd given away all but two. And I'm like, No, I'm hanging on to these two.

Clockwise from upper-left: Bluepoint's Shadow of the Colossus PS4 remake, The Last Guardian, and two teaser images for GenDesign's first post-Sony game, an untitled project known as "Project: Robot." | Images: Sony Interactive Entertainment, GenDesign

20 years later

Following Shadow of the Colossus' PS2 release in 2005, Sony brought the game back as a PS3 remaster in 2011, and then again as a PlayStation 4 remake in 2018.

After wrapping his work on Shadow of the Colossus, Ueda went on to direct a third game for Sony, The Last Guardian — the story of a child befriending a giant creature instead of attacking a series of them. He left the company in 2011 and finished the project through a new studio he founded, GenDesign. In 2024, GenDesign teased its first post-Sony project, an untitled game referred to as Project: Robot.

Kaido left Sony in 2012 and now works as an independent developer, recently announcing a retro-inspired action game called Saka-Doh: The Reversal Arts in which you attack while suspended from a flying helicopter. Kobayashi left Sony in 2011 and calls himself "half-retired," continuing to work as an adviser and board member for various game companies.

Looking back now after 20 years, they ponder what they might do differently if they could do it all over again.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): I feel like I really gave it my all, and that's why we were able to make a good game. I feel we accomplished everything we set out to do.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): I do notice the finer motion and graphics details, but honestly, I'd rather not revisit that part. I don't really want to look at it anymore. If I did, I'd probably want to fix all sorts of things. At the time, we did our absolute best within the limited time frame, platform, and hardware capabilities, so I'm satisfied. [...] In the past, I always thought, We could have done more, but after 20 years, I can appreciate it for what it is.

Yasuhide Kobayashi (executive producer, SCEJ): I don't know if this is really realistic, but I would want to go back and actually complete the whole package. Not just include the 16 enemies that made it into the final game, but extend the schedule and get all of the planned content in there. I'm 20 years older now and life is kind of coming full circle for me, I guess. Even though I'm older now, I guess you could say I'm more foolish than before.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): I don't want to dwell on the past, but if it were possible, I think we would have been a bit kinder to the player and improved the player experience.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): In hindsight, I would have pushed harder for a bigger budget.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): That's true. If we'd known it would be highly acclaimed, we definitely would have [negotiated for a bigger budget].

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): Honestly, I felt like I was sacrificing my soul to get our budget approved. Knowing in advance would have given me more confidence from the start, and I could have negotiated more effectively.

[Asked how they feel they have changed as game developers over the past 20 years, Ueda and Kaido describe different paths.]

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): I now have to handle management and business operations, too. That's the main difference. Comparing the Ico team to my current team, GenDesign, the biggest change is that my hands-on workload has decreased dramatically. During Ico and Shadow of the Colossus, I handled almost everything myself except programming and music. It wasn't quite that intense for The Last Guardian, and hasn't been quite that intense for our current title, but I still do some hands-on work. [...] I've said it repeatedly in prior interviews [that I'm less hands-on now], but it doesn't seem to get through. [laughs] The fact remains that my games have taken a long time to release, so I accept that this is what leads to the public's impression of me. [...]

If asked whether I'd do level design like Ico's today, I don't think I would. Because now I believe every shape and placement must have meaning. Ico was made more intuitively, prioritizing visuals first. I think that breathing room and flexibility led to its acclaim, but now, I'm more pragmatic. I resist coming up with ideas based solely on intuition. [...] While gaining experience has its benefits, I think there are drawbacks, too. There was a time when youthful energy allowed us to take on reckless challenges.

Kenji Kaido (line producer, SCEJ): I haven't changed at all. I've worked as a planner, director, producer, and project manager, but I don't think my approach to making games needs changing. I have a good balance of logic, passion, and intuition, so maybe I'm in a state where I don't need to evolve... I'm like a coelacanth [a fish known as a "living fossil" that hasn't changed for over 400 million years] — no need to evolve.

What came next

Curious how six people interviewed in this story felt about the team's next game, The Last Guardian, and its decade in development? And who didn't want to move the game to PS4? Click through!

Leaving a legacy

Between the critical praise, the awards, the sales, the remaster and remake, and the game's lasting impact on fans, Shadow of the Colossus far surpassed the targets Sony had set for it. Yet its legacy may be most clearly defined by how the game has inspired other developers. From indie games like Praey for the Gods and The Pathless to blockbusters like The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, Shadow of the Colossus' influence can be felt across the industry — even at times when players might not expect it, much like Battlefield 1942, Sam Raimi's Spider-Man, and other works inspired Ueda 20 years ago.

Kyle Shubel (producer, SCEA): The one thing I will say about Shadow — I'm 30 going on 31 years in making video games. I've released 150 SKUs in that time, easily. The one I always go back to as the favorite that I worked on was Shadow. I've had some fun games, but Shadow was amazing, and it was topical, and it was so ahead of its time when it released.

John Hight (director of external production, SCEA): It definitely influenced a lot of developers. [...] When I went to Blizzard Entertainment and I was responsible for World of Warcraft, a lot of the encounter designers — the people who would design the miniboss battles and the raid battles within World of Warcraft — would refer to Shadow of the Colossus in some of the battles, and even, there became this escalation of the size of a boss in WoW. They would talk about, "Yeah, you got to be like Shadow of the Colossus," where sometimes you feel like you're just beating up on the toenail of a giant.

Shawn Layden (vice president of international software development, SCEE): It told a majestic story with some heroics and some pathos and some tragedy and some magic, which kind of, I guess, describes most of Ueda-san's oeuvre. A little tragedy, a little magic. [...] It's just a great reminder to me about how really wonderful that whole PlayStation 2 era was in the different games we had and the variety. We haven't seen that since. It's all kind of tapered off to a world where we just play GTA, [Call of Duty:] Warzone, and Fortnite.

Fumito Ueda (director, SCEJ): Fundamentally, the root of my inspiration is making games I want to experience myself. [...] I create by thinking about what would be exciting and fun to experience in the real world. Experiences like clinging to something colossal, or riding a horse. [...]

I believe everyone shares these fundamental sensations. For example, in our daily lives riding cars, bikes, or trains, some people must think, I want to ride a horse. Others look up at tall buildings and think, I want to climb that. I'm just expressing those feelings [through my games]. While it's flattering to be called unique, I also think, Everyone likes this kind of thing, right? I think people fundamentally enjoy this. I think that's why I challenge myself to make them happen.

[All quotes above from Kenji Kaido, Yasuhide Kobayashi, Fumito Ueda, and Kow Otani were translated from Japanese. 10/14 update: We have corrected the name of the neighborhood Nakano-sakagami to read "Nakano-sakaue."]